Term Limits: Unknown in Ethiopia

The bright stars set against the dark night above Mount Entoto must have been a spectacular  sight to the aging monarch from Ankober. A devoutly religious man, he woke up early in the morning to recite the Psalms of David before tending to the affairs of his ancient yet infant empire. Having pulverized a recently united, desperate, and foolhardy European power, the brilliant warrior literally and figuratively stood on top of his nation. With his back turned to an ancient highland past and his navel to an equally historic lowland south that would soon fall under his empire, he observed his garrisons camped on the frosty hill that stood 10,000 feet above sea level. They were armed to the teeth with weapons seized from a humiliated Italy and also supplied by European powers with dubious intentions; prepared to respond to the steady beating of the Negarit, ready to act at the monarch’s bidding, and ready to push Ethiopia’s frontiers to her limits.

sight to the aging monarch from Ankober. A devoutly religious man, he woke up early in the morning to recite the Psalms of David before tending to the affairs of his ancient yet infant empire. Having pulverized a recently united, desperate, and foolhardy European power, the brilliant warrior literally and figuratively stood on top of his nation. With his back turned to an ancient highland past and his navel to an equally historic lowland south that would soon fall under his empire, he observed his garrisons camped on the frosty hill that stood 10,000 feet above sea level. They were armed to the teeth with weapons seized from a humiliated Italy and also supplied by European powers with dubious intentions; prepared to respond to the steady beating of the Negarit, ready to act at the monarch’s bidding, and ready to push Ethiopia’s frontiers to her limits.

His beloved second wife, not-so-lovely-to-look-at-but-a-must-have for any empire builder, shared her husband’s dreams of southern conquest but had her eyes set on the hot springs a few miles south. The Gondarine arthritic who couldn’t stand Entoto’s chilly nights spoke rarely, but when she did, her words resonated in her husband’s heart and in those of her enemies—“I am a woman…I do not like war…[h]owever, I would rather die than accept your deal” (rejecting Count Antonelli’s interpretation of the Wechale Treaty). On matters relating to palace intrigue and power play the monarch turned to her wisdom which the Light of Ethiopia supposedly dispensed with clairvoyant precision but which ultimately failed to serve her own end.

The emperor was no humanitarian—like George Washington a century earlier, the Ethiopian nation builder owned slaves and never considered ending ownership of human chattel. As the 19th Century drew to a close, the Ethiopian ruler’s dreams were unrequited and his ambition to expand Ethiopia’s frontiers to the south, southeast and southwest frontiers were only stopped by the ubiquitous British and French whose dreams to control the headwaters of the Nile would have placed those territories under the British Empire (extending from the Sudan and Kenya); French Legion d’Honneur outposts as far inland as Asbe Teferi; and the Brits and the fascists duking it out in the Ogaden. Through sheer will, King of Kings Menelik II struck fast and hard and brought in formidable people and fertile lands within the confines of the emerging empire.

Conquest is a bitter affair for the conquered—men die defending their villages, women are impregnated by foreign DNA, and their children are turned into slaves, caretakers of the offspring of conquistadors. Our history books and numerous unpublished masters and doctorate theses stacked on the shelves of AAU recount the countless wealth that flowed north following the conquest of the Oromo and Southern lands—grain, livestock, ivory, gold, and yes, human chattel. Clearly, the inclusion of these lands and people into Ethiopia resulted in an exponential economic windfall for the empire. It also added to the nation a wealth of cultures some extremely rich in democratic traditions and thousands of miles of buffer zones contiguous to the Indian Ocean that served to limit expansionist ambitions connived at the 1884 Berlin Conference as well as irredentist zeal of the remnants of the Ottoman Empire. The monarch handed to his predecessor(s) an Ethiopia spatially, demographically, militarily, and economically unimagined by the two Kassas before him. And for that, Ethiopia is today and will always be a power to be reckoned with.

But frontiersmanship always comes to a halt, as it must. Warriors at times engage in self-destructive behavior—they cross rubicons and take on more that they can peacefully administer. Campaigns also meet “natural deaths”—rivers, seas, cliffs, impenetrable forests, and mountain ranges—God’s barriers that allow soldiers to finally sheath their swords and to transform them into plough shares. Frontiersmanship takes on a new annotation: the collective aspiration of warriors and their descendants to secure a peaceful future for their children. For many nations, the process of creating political stability takes centuries.

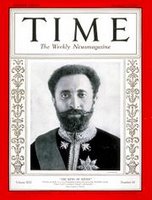

"Apart from the Kingdom of the Lord there is not on this earth any nation that is superior to any other” Haile Selassie I

34 Years

Think what you must about the legacy of His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I but the important role he occupies in Ethiopian history cannot be denied. In November 1930, at the time of his coronation, the 38-year-old assumed a nation without access to the sea, a written constitution, with a medieval economy, inexistent infrastructure, and militarily vulnerable—a reenergized fascist Italy breathing its putrid colonial breath across the Mereb River and who would soon use chemical-biological weapons to march into his capital in its zeal to avenge its humiliation in Adwa. But the emperor did it—in just 34 years, the son of Menelik’s favorite cousin created a strong unitary state, reclaimed Mereb-Melash and an outlet to the sea, helped create the OAU and ECA and brought their headquarters to Ethiopia, and shepherded his nation through the untenable world of non-alignment. And these are only a few of his achievements.

But HIM’s claim to power (essentially, descendance from a dubious union that resulted from an act of Judaic rape) and rule were certainly not democratic. By the end of the 1960s, a new direction was sorely needed and the emperor, for all sorts of reasons, was simply unable to read the pulse of his people. HIM’s undoing was his failure to imagine an Ethiopia without the Solomonic Dynasty and in that sense he was no different than Menelik—for all his accomplishments, he failed to bestow to his vassals the greatest gift he could have imparted to them: a system of governance that allows Ethiopians to have a say in their country’s future.

Ploughshares into Swords

Despite the uplifting Ityopia Tikdem rallying cry, sanguinous Mengistu Hailemariam drenched his country in rivers of blood unseen in the nation’s history. He did so by convincing young men to join death squads that hunted and cut down those who dissented. By creating a culture of mass flight out of the country, Mengistu (and his predecessor Meles Zenawi) turned Ethiopians into refugees who live as second-class citizens throughout the world. Mengistu’s end, like his predecessor’s was identical—he was forced to abandon power by those who wielded superior military power.

Despite the uplifting Ityopia Tikdem rallying cry, sanguinous Mengistu Hailemariam drenched his country in rivers of blood unseen in the nation’s history. He did so by convincing young men to join death squads that hunted and cut down those who dissented. By creating a culture of mass flight out of the country, Mengistu (and his predecessor Meles Zenawi) turned Ethiopians into refugees who live as second-class citizens throughout the world. Mengistu’s end, like his predecessor’s was identical—he was forced to abandon power by those who wielded superior military power.

The more things change the more they stay the same. Since 1995, Ethiopia’s leadership has told us that unlike prior regimes it has received the consent of its people to rule over them. It has told us over and over again its claim to power is based on expressed consent it received in three election cycles. Repeated United States Department of State Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, by in large unopposed and unresponded to by Ethiopia, informs the conclusions we draw that those who dared to disagree with the EPRDF’s prescriptive agenda in the constitutional, political (domestic and foreign policy) and judicial realms have either paid for their disagreement with their lives or received brutal physical and/or psychological torture in the country’s notorious detention centers. When dissenters enjoy access to the public (like the leaders of the Coalition of Unity & Democracy), the EPRDF has used its security, judicial, and information apparatus to mete out its version of justice through surveillance, prolonged detention without change, presentation of false charges, and outright defamation of character.

And so we return to the warrior afoot on Mount Entoto. Empires are built by individuals who allow their dreams to seep beyond the frontiers they’ve inherited; to reach levels of expansion and power unfathomed by their predecessors. When judging these characters history’s eyes should nonetheless be fair—acts of barbarism of the heretofore must not be free of condemnation but revision and attendant reproach must be fair—after all, if we use past persecution practiced by the ancien order as a yardstick to measure the ability of a people to ultimately create a democratic society, America’s barbaric acts against native Americans and African slaves would render her system of individual liberty, separation of powers, and independence of judiciary, ideals on which we model our ideals of democracy, negligible.

The yardstick we use is one that contemplates the future—the question of whether a particular society has learned from its past mistakes and whether it uses those lessons to devise policy that serves the interests of Ethiopians and Ethiopians alone. For starters, the political party Ethiopian voters should support is not one that merely proves its superiority to the EPRDF by listing a litany of promises to adhere to lofty democratic ideals (not difficult to do so) but one that also runs on a single commitment: to limit the number of years it intends to rule.

Yes, my friends, the more things change the more they stay the same. Ethiopians have been governed by a group of heretics who replicated Joseph Stalin’s rule in Ethiopia and now by former Albanian Communists who waive a sickly and withered democratic banner as a pretext to rule in perpetuity. Monarchs have come and gone as have, and eventually will, “revolutionaries” of various types—the “socialists” and the “democrats”—but what remains constant is the curse that has befallen this nation of 70 million people of never having been blessed with rulers who have relinquished power voluntarily.

- We look forward to discussing Dr. Berhanu's Goh. ET Wonq's suggestion, like her blog, is brilliant. We can't promise acuity but will do our best to contribute to the Wonq's attempt to engage all of us in a productive (and yes, democratic) exercise.

- Enkwan le berhane lidetu aderesachuh. (Merry Ethiopian Christmas)

- May the new Gregorian year bring peace to the good people of Ethiopia.